This 4 section series is based on a recent paper (Andringa & Denham, 2021) in which we outline the basics of core cognition starting from the demands to being and remaining alive and maximizing viability of self and habitat. In it we derive core cognition and its two main modes, coping and co-creation, from first principles.

A living entity is different from a dead entity because it self-maintains this difference. To live entails self-maintaining and self-constructing a “far from equilibrium state”. The work of Prigogine (1973) showed that, for thermodynamic reasons, such an inherently unstable system can only be maintained via a continual throughput of matter and energy (e.g., food and oxygen). Death coincides with the moment self-maintenance stops. From this moment on, the formerly living entity moves towards equilibrium and becomes an integral and eventually indistinguishable part of the environment.

A living entity “is” — exists — because it “does”: it satisfies its needs by maintaining the throughput of matter and energy by “adaptively regulating its coupling with its environment so that it sustains itself” (Andringa et al., 2015; Barandiaran, Di Paolo, & Rohde, 2009 p. 8). An autonomous organization that does this is called a “living agent” or an agent for short (Barandiaran et al., 2009). Note that we refer to an agent when the text pertains to life in general and is part of core cognition. Where we specifically refer to humans we use the term “person”. The term “individual” can refer to both, depending on context.

Life is precarious (Di Paolo, 2009), in the sense that it must be maintained actively in a world that is often not conducive to self-maintenance and where both action and inaction can have high viability consequences (including death). We refer to behavior as agent-initiated context-appropriate activities with expected future utility that counteract this precariousness and minimize the probability of death. Behavior is always aimed at remaining as viable as possible, since harm — viability reduction — can more easily end a low-viability than a high-viability existence.

A pattern of behaviors that effectively optimizes viability leads to flourishing, while a pattern of ineffective or misguided behaviors leads first to languishing and eventually to death. Life is “being by doing” the right things (Froese & Ziemke 2009, p. 473). Viability is a holistic measure of the success or failure of “doing the right things”, since it is defined as the probabilistic distance from death: the higher the agent’s viability, the lower the probability of the discontinuation of life. A walrus that falls off a cliff may be perfectly healthy, but it has zero viability, since it will die the moment it hits the ground. While healthy, it is in mortal and inescapable danger, and hence unviable. In general, threat signifies a perceived reduction of contextappropriate behavioral options that allow the agent to survive. Maximizing viability (flourishing) and minimizing danger (survival) constitute basic motivations of life. In fact, we call any system cognitive when its behavior is governed by the norms of the system’s own continued existence and flourishing (Di Paolo & Thompson, 2014). This is also a reformulation of “being by doing”.

Agency entails cognition: behavior selection for survival (avoiding death) and thriving (Barandiaran et al., 2009) (optimizing viability of self and habitat). We have argued that cognition for survival is quite different from cognition for thriving (Andringa et al., 2015). Cognition for survival is aimed at solving problems, where a problem is any perceived threat to agent viability, interpreted as a pressing need that activates reactive behavior. We called this form of cognition coping. In humans, (fluid) intelligence is a measure of problem-solving and task-completion capacity and manifests coping. The objective of coping is ending/solving the problems that activated the coping mode, so ideally coping is a temporary state. We refer to the problem-solving ability, including successful test and task completion ability (Gottfredson, 1997; van der Maas, Kan, & Borsboom, 2014), as intelligence.

However, when the agent’s problem solving is inadequate and problems are not solved and are potentially worsened or increased, the perceived viability threat remains activated and the agent is trapped in the coping mode of behavior. A coping trap keeps the agent in continued threatened viability, and hence in behaviors aimed at short-term self-protection in suboptimal states that are far from flourishing. Maslow (1968) calls this deficiency (D) cognition, since it is ultimately activated by unfulfilled needs. It is a sign that the intelligence of the agent failed to end (solve) problem states.

While the coping mode of behavior is for survival, the co-creation mode is for flourishing. Successful coping leads to solved problems and satisfied needs, and hence to its deactivation. Therefore, co-creation is the default mode of cognition and coping is — ideally — only a temporary fallback to deal with a problematic situation. Continued activation is the success measure of the co-creation mode and avoiding problems (or dealing with them before they become pressing) is, therefore, the main objective of co-creation. It is essentially proactive behavior (thus not just “proactive coping”, since successful coping leads to its deactivation). Maslow (1968) refers to co-creation as being (B) cognition, and we described it as pervasive optimization and “generalized wisdom”, for reasons which will become apparent. The objective of co-creation is pro-actively producing indirect viability benefits through self-guided habitat contributions that improve the conditions for future agentic existence.

This is known as stigmergy: building on the constructive traces of past behaviors left in the environment (Doyle & Marsh, 2013; Gloag et al., 2013; Heylighen, 2016b; 2016a) and that, in the aggregate, gradually increase habitat viability. This expresses authority as a shaping force in the habitat (Marsh & Onof, 2008), via influencing others through habitat contributions. Habitat is defined as the environment from which agents can derive all they need to survive (and thrive) and to which they contribute to ensure long-term viability of the self and others.

Habitat viability is a measure of the potential of the habitat to satisfy the conditions for agentic existence (i.e., satisfied agentic needs). For example, a habitat can be deficient in the sense that its inhabitants continually have unfulfilled needs (and hence are in the coping mode). The habitat can also be rich, so that pressing needs can easily be satisfied and co-creative contributions can perpetuate and enhance habitat viability.

The biosphere grew from fragile and localized to robust and extensive, so we know beyond doubt that life on Earth is, in the aggregate, a constructive force. It is the co-creation mode’s contributions to habitat viability that explain this. In fact, the biosphere can be seen as the outcome of stigmergy: the sum total of all agentic traces left in the environment since the origin of life (Andringa et al., 2015). Co-creation and generalized wisdom as the main cognitive ability drive the biosphere’s growth and gradually increase its carrying capacity: the sum total of all life activity in the biosphere. This makes co-creation the most authoritative influence on Earth. Coping is also an important authoritative influence, but it is limited to setting up and maintaining the conditions for pressing need satisfaction.

Figure 1 presents the co-dependence of acting agents on their habitat. The habitat comprises the aggregate of agentic activities, but is not an actor itself. Hence, a viable habitat is composed of the sumtotal of previous co-creative agentic traces that form a resource to satisfy the conditions on which current agentic existence depends. This entails that, signified by the question marks, agents should be aware not only of their own viability, but also of habitat viability. In fact, we have argued (Andringa, van den Bosch, & Weijermans, 2015) that early, primitive life forms were yet unable to separate self from the co-dependence of self and habitat. This leads to an “original perspective” on the combined viability of agent and habitat, which allowed their primitive cognition to optimize the whole, while addressing selfish needs and creating ever better conditions for agentic life. This can be termed pervasive optimization and it expresses an emergent purpose of life on Earth to produce more life. Albert Schweitzer (1998) formulated a slightly weaker version of this “I am life that wills to live in the midst of life that wills to live.”

Pervasive optimization is the driver of well-being. We propose that successful well-being, with a focus on ‘being’ and hence interpreted as a verb, can best be understood as a co-creation process leading to high viability agents, increased habitat viability, and long-term protection and extension of the conditions on which existence depends.

The two modes of behavior have quite different impacts on the habitat and, by extension, the biosphere. The coping mode is aimed at protecting and improving agent viability with whatever means the agent has access to. Since the objective is avoiding death, the motivation is high, which entails that habitat resources can be sacrificed for self-preservation purposes. Inadequacy can be defined as the tendency to self-create, prolong, or worsen problems that keep an agent in the coping mode. When a habitat is dominated by inadequate agents, as is characteristic of a social level coping trap, habitat viability cannot be maintained, let alone increased. From the perspective of coping, life is at best a zero-sum game.

Alternatively, adequacy can be defined as the ability to avoid problems or end them quickly so that coping is effective and rare. Now co-creation is prevalent so that habitat viability is protected, carrying capacity increases, and long-term need satisfaction is secured. Co-creation is, like the term suggests, a more than zero sum game. This is, as argued above, the true basis of well-being. Due to its lack of “co-creation”, coping protects lower levels of well-being and, at best, resolves (or otherwise takes care of) viability threats (in the sense of removing symptoms of low well-being), while co-creation allows both agent and habitat flourishing.

The inadequacy-adequacy dimension might underlie the proposed single dimension of psychopathology termed p (Lahey et al., 2012; Caspi and Moffit, 2018). This has been conceptualized as “a continuum between adaptive and maladaptive functioning”, “successful versus unsuccessful functioning”, a disposition for negative emotionality or impulsive responsivity to emotion, and unrealistic thoughts that manifest in extreme cases as delusions and hallucinations (Smith et al., 2020). All descriptions fit with our interpretation of inadequacy as the tendency to self-create, prolong, or worsen problems and adequacy as the ability to avoid problems or end them quickly.

Welzel and Inglehart (2010) argue, from the perspective of cultural evolution, “that feelings of agency are linked to human well-being through a sequence of adaptive mechanisms that promote human development, once existential conditions become permissive”, which is a formulation of the dynamics of Figure 1. They argue that “greater agency involves higher adaptability because for individuals as well as societies, agency means the power to act purposely to their advantage”. This uses the concept of agency as a measure of the ability to self-maintain viability, which is related to adequacy.

Living agents, per definition, need to express behavior to perpetuate their existence. And with every intentional action, the agent implicitly relies on the set of all that it takes as reliable (i.e., true in the sense of reflecting reality as it is) enough to base behavior on. We refer to this set as the agent’s worldview. A worldview should be a stable basis, as well as developing over time because it is informed by the individual’s learning history. An agent’s worldview informs its appraisal of the immediate environment. This may be an appraisal of its viability state: whether the habitat is safe or not, or whether it judges the current situation as manageable, too complex, or opportunity filled.

These are basic appraisals shared by all of life that seem to be reflected in the psychological concept of core affect (Russell, 2003). Core affect is a mood-level construct that combines the axis unpleasureable-pleasurable with an arousal axis spanning deactivated to maximally activated. It is intimately and bidirectionally linked to appraisal (Kuppens, Champagne, & Tuerlinckx, 2012; van den Bosch, Welch, & Andringa, 2018) and refers directly to whether one is free to act or forced to respond: whether one can co-create proactively or has to cope reactively. Hence appraisal is a worldview-based motivational response to the perceived viability consequences of the present state of the world. It is motivational, but not yet action. As such appraisal resembles Frijda’s (1986) emotion definition as ‘action readiness’. Which fits with the notion that all cognition is essentially anticipatory:

“Cognitive systems anticipate future events when selecting actions, they subsequently learn from what actually happens when they do act, and thereby they modify subsequent expectations and, in the process, they change how the world is perceived and what actions are possible. Cognitive systems do all of this autonomously.” (Vernon 2010, pp. 89).

The anticipation of the development of the world (comprising of self and environment) refers back to what we earlier introduced as the “original perspective” on the combined viability of agent and habitat, which allowed the first life forms to optimize the whole, while addressing selfish needs and creating ever better conditions for more agentic life. Core affect is a term adopted from psychology (Russell, 2003) that we here generalize to all of life. Core affect is a relation to the world as a whole and not a relation to something specific in that world. Like moods, core affect does not have (or need) the intentionality (directedness) of emotions and it is, unlike emotions, continually present to self-report (van den Bosch, Welch, & Andringa, 2018).

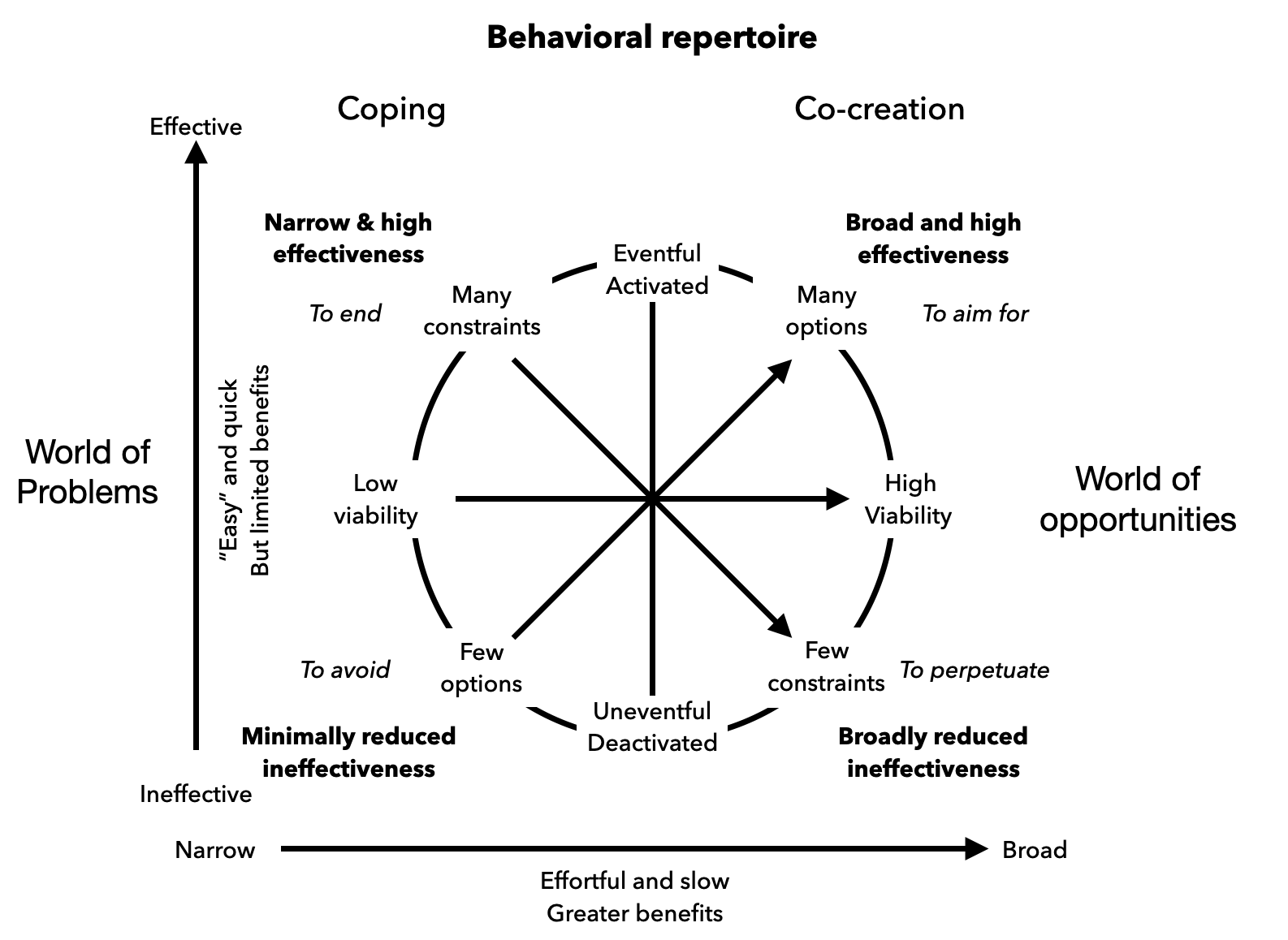

The human worldview is, of course, filled with explicit and shared beliefs, opinions, facts, or ideas interpreted with and filtered by experiential knowledge. This worldview informs whether the situation is deemed dangerous or not (whether avoidance or approach is appropriate). This holds also for a general agent: when the agent judges the situation as safe it can express unconstrained natural behaviors since it has to satisfy few constraints. If the situation is safe and opportunity-filled, it can be interested and learn. But if the situation imposes many constraints, it tries to end these by establishing control. And in a deficient environment the agent is devoid of opportunities (which in humans may correspond to boredom or, in case of lost opportunities, sadness). Core affect then is expressed as motivations to avoid or end (coping) or motivations to perpetuate or to aim for (co-creation). We have depicted this in Figure 2.

Appraisal of reality refers to the behavioral consequences of the current state of the world and it is a form of basic meaning-giving that activates a subset of context appropriate behavioral options (van den Bosch, Welch, & Andringa, 2018). This leads to motivation as being ready to respond to the context appropriately. We define the set of all possible – appraisal and worldview dependent – behaviors as the behavioral repertoire. The richer the behavioral repertoire, the more diverse context appropriate behaviors the agent can exhibit. The more effective its behavioral repertoire, the more effective it becomes in realizing intended outcomes and the more adequate the agent is. Conversely, the less effective the context-activated behaviors, the more inadequate the agent is. Learning either reduces the ineffectiveness of behaviors or it expands the behavioral repertoire.

Expanding the repertoire results from an individual discovery path through a representative sample of different environments and interactive learning opportunities. Broadening is effortful and potentially risky but ultimately rewarding. Fredrickson’s (2005) broaden and build theory fits here by proposing that positive emotions – indicating the absence of problems and hence co-creation – help to extend the scope of behavioral options. This type of learning leads to individual skills that are, through the individual discovery path, difficult to share. This manifests in humans as implicit or tacit knowledge (Patterson et al., 2010) and well-developed agency.

Reducing the ineffectiveness of behaviors is essential in problematic (coping) situations. This may entail adopting, through social mimicry, the behaviors of (seemingly) more successful, healthy, or otherwise attractive agents. The adoption of presumed effective behaviors manifests shared knowledge. Mimicry is a quick fix and works wherever and as long as the adopted behaviors are effective. As a dominant learning strategy, mimicry leads to a coordinated situation of sameness and oneness. The coordinated agents make their adequacy conditional to the narrow set of situations where the mimicked behaviors work. These agents may be intolerant to others who frustrate sameness and oneness. They may express this intolerance by selecting behaviors that enforce social mimicry on non-mimickers. The more they feel threatened, the more they feel an urge to restore the conditions for adequacy and the more intolerant to diversity they are. In humans this is expressed as the authoritarian dynamic (Stenner, 2005).

This discourse leads to a selection of core cognition key concepts with definitions.

Here we develop the structure of identity in terms of coping and co-creation adequacy. This leads to an enriched understanding of the interplay between coping and co-creation, and it demonstrates that the conceptual language of core cognition is a productive lens for approaching a well-studied psychological phenomenon.

Previously (Andringa, van den Bosch, & Wijermans, 2015) we have connected the existence of an individual’s unique identity to the self-maintenance of the living state. Here we develop the structure of identity in terms of coping and co-creation adequacy. This leads to an enriched understanding of the interplay between coping and co-creation, and it demonstrates that the conceptual language of core cognition is a productive lens for approaching a well-studied psychological phenomenon. What we describe here connects intimately to the different perspectives on the world that the two brain hemispheres, as described by McGilchrist (2012), produce: i.e., that the left-hemisphere is strongly connected to coping and the right hemisphere to co-creation (Andringa et al., 2015). Editorial constraints prevent us from developing this concept here in detail.

Berzonsky (1989), quoting Epstein, describes

a theory that the individual has unwittingly constructed about him- or herself as an experiencing, functional individual … it contains major postulate systems for the nature of the world, for the nature of the self, and their interaction. Like most theories, that self-theory is a conceptual tool for accomplishing a purpose. Major purposes are to optimize the pleasure/pain balance of the individual over the course of a lifetime … and to organize the data of experience in a manner that can be coped with effectively.

Learning to optimize the pain/pleasure balance fits very well with optimizing well-being of the self through self-development of a worldview and an adequate behavioral repertoire for coping and co-creation. According to Berzonsky, the effectiveness of a self-theory can be measured in terms of whether it helps “to solve the personal problems it was constructed to handle [and …] serve as a framework within which experience and […] relevant information can be meaningfully organized and understood” (1989). We refer to this (partial) effectiveness as (partial) adequacy (see section 1 “Well-being and adequacy”) use that to derive the main structure of identity.

Figure 2 in Section 1 described the development of an agent’s behavioral repertoire. In this section we adapt it towards how humans deal with life’s challenges and problems (and indirectly to identity research). In [Section 2](basics/2-coping-and-co-creation/) we described two main strategies to make the world more predictable and hence more manageable. Coping aims to make the world more predictable by reducing its complexity and creating systems (of agents or things) with more predictable behavior, thus bringing threats-to-self under control and promoting security. Co-creation makes the world more predictable by promoting unconstrained natural behavior and easy need satisfaction, through promoting and communicating efforts that facilitate and maintain habitat viability and overall safety. We defined a highly adequate agent as one that can prevent most problems, and quickly and effectively solve what cannot be prevented. Problems (and challenges) that cannot be prevented or solved can be controlled (suppressed) or avoided. These four strategies – preventing, solving, controlling, and avoiding – can be included in Figure 2 in Section 1 to yield Figure 3 below.

Four attitudes toward problems and challenges (on the main axes), coupled with broad strategies (on the circle), effects on the world, and behavioral (in)effectiveness. The dashed arrows represent life’s key demands: maintaining and increasing viability of self and habitat (Part 1, Figure 1). Alternatively attending to both demands implements core cognition.

Four attitudes toward problems and challenges (on the main axes), coupled with broad strategies (on the circle), effects on the world, and behavioral (in)effectiveness. The dashed arrows represent life’s key demands: maintaining and increasing viability of self and habitat (Part 1, Figure 1). Alternatively attending to both demands implements core cognition.

The main horizontal axis denotes preventing problems (associated with wisdom) as the highest manifestation of self-direction since it leads to high viability of self and habitat Figure 1 in Section 1). Its fallback strategy is controlling or reducing (unprevented) problems through social mimicry (Chartrand & van Baaren, 2009) as a manifestation of low self-direction. This is a situation where persistent problems require great effort to handle but are not necessarily successfully controlled and signify low viability. The vertical axis reflects solving problems (associated with intelligence) as a way to assert oneself or, alternatively, avoid them as a way of adapting without changing the situation.

The four quadrants of Figure 3 correspond directly to those in Table 3 (see below), where the combination of attitudes towards problems and challenges define each of the four table entries that we are going to connect to matching identity statuses (indicated in brackets). In each quadrant we first give a short description in terms of adequacy, and secondly, we describe the associated worldview.

| Controlling | Preventing | |

|---|---|---|

| Solving | Controlling & Solving (Identity foreclosure) Agents modify the world (with great effort) to prevent being confronted with their own inadequacies by promoting a suitable form of sameness and oneness through social mimicry (see Part 1, Coping) which creates an in-group with shared rules (and narratives). Their shared worldview enhances in-group effectiveness, but cannot claim realism since it excludes out-group perspectives because it primarily values sameness and oneness. |

Preventing & Solving (Achieved identity) Agents are both adequate problem preventers and problem solvers because they continually self-acquire the skills to benefit most from the possibilities of the world. This allows them to exhibit more or less unconstrained natural behavior. Their co-creation and coping effectiveness, and hence life-success, prove they have developed and continually maintain a realistic worldview. |

| Avoiding | Controlling & Avoiding (Identity diffusion) Agents have neither co-creation nor coping skills and can only maintain an illusion of agentic adequacy through avoiding challenges or engaging in damage control by behavioral mimicry of (seemingly) successful others. They live in a world of intra- and extra-agentic forces that they neither comprehend nor control, and their worldview is incoherent and inconsistent. |

Preventing & Avoiding (Identity moratorium) Agents aim to co-create or select a world where they are not inadequate because it promotes easy need satisfaction and unconstrained natural behavior. They live in a world that they mostly understand and can handle, but tend to be bothered by long-term problems, which periodically surface, because they lack the skills to address them effectively. In addition, they are blind to the power of complexity reduction and control strategies. |

In Table 3, the set of behaviors still pertains mainly to general agents, since we limited ourselves to the generalized concepts and formulations derived in Part 1. In the next sections we will introduce, first, the defining two dimensions of the human identity concept, and secondly, we will describe each of the four described identity statuses in relation to what we outlined in Table 3.

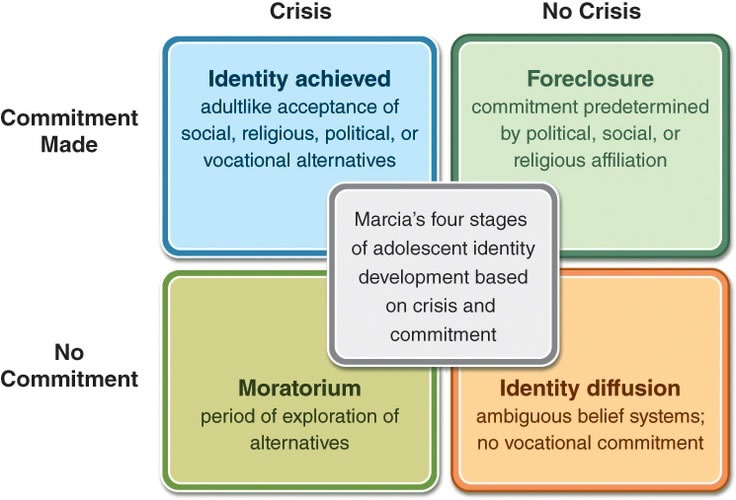

The modern identity concept James Marcia (1967) described late-adolescent development in terms of a transition from “the given” (the dependent) to the (independent) “givers,” and an identity (development) crisis. He described (1966) four identity statuses as combinations of high and low scores on two dimensions: stable commitments and (to use a modern formulation) deliberate self-exploration.

Stable commitments indicate that personal strategies are effective and, hence, that one can build – self-directedly – on traces left in the habitat (which is related to concepts like stigmergy and authority). Since effective strategies are further improved through experience, they do not have to be replaced. This leads to stable, albeit developing, life-strategies and a stable, and effective personality. In Figure 2 of Part 1, this corresponded to an “upward’’ move towards a more effective behavioral repertoire.

Deliberate self-exploration and the development of a self-constructed theory of me as an actor in the world is a requirement for the development of a unique self, rather than an identity based on values and beliefs adopted uncritically and unchanged from others (mimicking). The process of deliberate exploration of me-as-an-actor-in-the-world manifests as the broadening of the behavioral repertoire. In Figure 2 of Part 1 we noted that broadening the behavioral repertoire is more arduous and slower than making it narrowly more effective through mimicking behaviors of those more effective, healthy, or otherwise attractive individuals. But since the broadening contributes to co-creation capacity, it offers higher long-term benefits, and is a preferred choice for individuals who have learned to value co-creation. Valuing these benefits requires the development of co-creation’s basic strategy of discovering, and later using, the unconstrained natural behavior of self, others, and the wider habitat.

The shaping of a unique self occurs on the basis of shared or consensually adopted values, beliefs, and strategies to bootstrap self-development. Actualizing a unique self requires a shift in one’s perceived locus of causality (PLOC) from external (like social mimicry) to internal: “The more internalized a value or regulation, the more it is experienced as autonomous or as subjectively located closer to the self” (Ryan & Connell, 1989, p. 750; Andringa, van den Bosch, & Vlaskamp, 2013). It also manifests self-direction.

PLOC internalization is not so much a rejection of previous values, beliefs, and strategies, but a refinement of these by allowing individual experiences to be enriched and generalized. Hence, they can be applied more flexibly (less rigidly), more context-appropriately (i.e., more realistically), and more proactively with long-term benefits; this is a change from explicit rule following to the use of experience-based tacit knowledge and self-direction. The combined changes of PLOC from external to internal, from explicit to tacit knowledge use, and from group to individual authority, entail emerging self-direction and liberation from self-limiting constraints, adopted via social mimicry, that warrant characterization as a self-exploration crisis.

Identity research uses past or current self-exploration crises as tell-tale indicators of identity development. In this paper, we connect negotiating or avoiding this crisis to the development (or not) of co-creation adequacy. More precisely, a self-exploration crisis does not indicate co-creation adequacy, but only a co-creation preference; the individual notices its benefit over coping, but is not necessarily adequate yet. Similarly, we connect stable commitments to coping or co-creation adequacy, and the absence of stable commitments to inadequacy. Commitments remain unstable until adequacy is reached. Table 4 shows this for the four identity statuses we outlined above. (Berzonsky, 1989; Erickson 1966).

Table 4

The four identity statuses

| No deliberate self-exploration Coping preference PLOC external / Low self-direction | *Deliberate self-exploration *Co-creation preference PLOC internal / High(er) self-direction |

|

|---|---|---|

| Stable commitments Adequate coping |

Identity foreclosed Self-exploration prevented through adoption of societal norms. **Focused on dealing with viability threats to self ** The world is unstable and dangerous and needs constant surveillance, control, and forceful efforts to prevent disintegration and becoming totally dysfunctional. Focus on enforcing complexity reduction of habitat and agent behavioral uniformity through promoting oneness and sameness. An effective, but limited behavioral repertoire. They only take responsibility for group-level endorsed actions and procrastinate when forced to self-decide. Characteristic insistence on others changing or adapting to protect themselves from exposing their inadequacies: forcing others to mimic them by encouraging or enforcing the adoption of their rules (and narratives). |

Achieved identity Self-exploration crisis negotiated, resulting in well-explored stable identity. **Effectively improving own and habitat viability ** World is full of opportunities and solvable problems and promotes self-development. Focus on opportunities of self and habitat. Self-actualization as an expression of a broad and effective behavioral repertoire. They take full responsibility for their actions and tend to address challenges as they come (which benefits development of self and habitat). Corresponds to what Maslow (1954) refers to as self-actualization. It is a state of maximal psychological health and self-development. And it fully implements core cognition. |

| No stable commitments Inadequate coping |

Identity diffusion Self-exploration avoided, in combination with a fluid or unstable self-identity. **Contributor to deficient viability of self and habitat ** The world is unpredictable and brutal, since actions and outcomes seem unrelated; responsibility for actions is not taken. They focus on strategies that mitigate (public exposure of) inadequacy. Little self-development. Behavioral repertoire is narrow and minimally effective. They take no responsibility for their actions because they can hardly predict the outcomes of their behaviors. Their development depends strongly on whether the environment is conducive for it or not. A rich and safe learning environment allows them to progress to the other quadrants, while an unsafe and deprived environment traps them. |

Identity moratorium Self-exploration crisis (still) in progress, not (yet) leading to a crystalized identity structure. Aimed at protecting the conditions for own existence The world is sometimes a problematic place but invites continued self-exploration and engagement. They focus on broadening their behavioral repertoire, mastering co-creation strategies and developing a unique identity. They take responsibility for self-initiated co-creative actions, but procrastinate or evade when faced with serious challenges. Avoidance of challenges deprives them of the learning opportunities to develop high coping skills. |

Note. Words in italics are the defining properties of the four types of identity statuses (based on Berzonsky, 1989). These identity-status-related core cognition features are in the normal font.

In the next four subsections we will derive the properties of the four identity statuses described in Table 4: achieved, moratorium, foreclosed, and diffusion. Our derivation is based on the framework described in Part 1, and in particular the four-pronged structure to deal with life’s challenges outlined in Figure 3 and Table 3. As has been confirmed (Berzonsky, 1993), we assume no gender differences.

An achieved identity signifies co-creation and coping adequacy: a rich and effective behavioral repertoire ensures that most problems are avoided, and problems that do occur are dealt with quickly and effectively so that co-creation can resume problem prevention. This involves the individual safely and effectively building on past efforts (stigmergy) that produce few unintended and adverse side effects. To the achieved identity the world is full of opportunities and solvable problems. And they can and do take responsibility for self-initiated actions.

Developmentally, the achieved identity emerges from a successfully negotiated self-exploration crisis that results in a well-explored stable identity and full self-direction. With the achieved identity comes the informational identity style that Beaumont and Pratt (2011, p. 174) summarize for achievers as follows:

… they address identity-relevant issues by being skeptical of their self-views, questioning their assumptions and beliefs, and exploring and evaluating information that is relevant to their self-constructions [hence making and keeping their worldview in accordance with the state of the world]. The use of an informational style is positively associated with strategic planning [which includes problem prevention], vigilant decision making, and the use of proactive and problem-focused coping [indicating effective coping and co-creation]. The informational style is also associated with such personal and cognitive attributes as autonomy, openness to experience, introspectiveness, self-reflection, empathy, a high need for cognition, and a high level of cognitive complexity.

These listed properties all facilitate high autonomy, strong self-development, and the effective real-world contributions characteristic of co-creation, as well as high well-being (Berzonsky & Cieciuch, 2016) and wisdom, as we have defined them in Section 2. All in all, this expresses both coping and co-creation adequacy.

Identity moratorium develops due to a preference for co-creation and coping inadequacy: a (fairly) broad behavioral repertoire ensures that many problems are avoided, but problems which do occur are often not dealt with quickly and effectively; the individual cannot (yet) rely on stable and reliable strategies (commit) and instead struggles to develop these. To the person with a moratorium identity, the world is a place for continued self-exploration and major problems. He or she experiences an ongoing self-exploration crisis and has a self-development focus that, despite efforts, does not yet lead to a stable identity structure, although it expresses a “limited commitment” (Berzonsky & Cieciuch, 2016) through its co-creation preference.

Although co-creation adequacy might not have been achieved, co-creation is still considered superior to coping and, hence, is the preferred strategy. This means that the person with a moratorium identity expresses the strengths of co-creation through a focus on contributing to a high-quality habitat, for which the person can take responsibility. However, the strengths of coping — control of problematic situations and effectively ending problems — are minimally expressed and might, when problem solving is structurally avoided, lead to toxic situations. This leads to less time for co-creating than the achieved identity status, and comfort, defined as an absence of apparent pressing problems, is highly valued.

People with a moratorium identity express many of the features of the informational identity style, but to a lesser degree due to their lower coping skills, which also leads to lower well-being than the achieved identity style (Berzonsky & Cieciuch, 2016).

Identity foreclosure is the identity status that is central for the next section, so we elaborate it in this subsection. Identity foreclosure combines co-creation inadequacy with adequate coping. Co-creation inadequacy leads to structurally unprevented problems, but coping adequacy ensures that these are managed with effort — i.e., controlled — so that they do not (usually) spin out of control. The concept of security, defined as threats brought and kept under control, describes this. The associated worldview is one of an unstable and dangerous world that needs constant surveillance, control, and the need for forceful efforts to prevent disintegration and becoming totally dysfunctional. This motivates the individual with a foreclosed identity more often than not (although limited meta-cognition ensures that they are unaware of this).

Identity foreclosure corresponds to prevented (foreclosed) self-exploration through the uncritical adoption of consensual norms (Berzonsky, 1989; Marcia, 1966) and social mimicry. The dominance of the coping mode leads to favoring in-group level rules and, in general, shared (explicit) knowledge over individual (implicit) knowledge. Foreclosed individuals aim to adopt and express shared rules and narratives with great diligence, and they actively promote the adoption of their shared worldview. Neither the body of shared rules nor the single shared worldview is explored since it is adopted on the basis of superficial effectiveness and social mimicry rather than deliberation on its effectiveness and context appropriateness. The associated worldview is therefore often at odds with actual states of reality, thus perpetuating the body of unprevented problems that have to be controlled.

The resulting strict adherence to the norm and an insistence of oneness and sameness — generating an ingroup — effectively curtails agent and habitat diversity. This is considered moral and responsible behavior because it is intended to manage the threats that keep the coping mode activated. Ironically, “foreclosed” individuals see little value in co-creation’s preventative strategies and in questioning its associated assumptions and beliefs. Instead, they view them as out-groups: individuals who violate sameness and oneness, and hence, frustrate coordinated coping. This means that the “foreclosed” individual is blind to (superior) strategies that might structurally prevent the problems they try so hard to keep from spinning out of control. Hence, more often than not, the threats and problems persist, which locks this identity status into a self-perpetuated coping trap.

Groups of foreclosed individuals manifest a social level coping trap that, through their insistence on coordinating the behaviors of others, threatens to dominate the habitat. Groups of foreclosed individuals have the only identity status that insists on others changing and conforming. Their (unspoken) motto is: “We are right and you have to adapt your behavior to match ours.” They feel righteous because they have no access to perspectives and worldviews other than their own, and they lack the tools to judge the merits of out-group insights. Hence, they see only potential harm in out-group strategies.

Worse, they are particularly insensitive to arguments more nuanced or personal than rule-following and other forms of social mimicry. In fact, they prefer cognitive closure (Webster & Kruglanski, 1994) in answering questions on a given topic, over continued uncertainty, confusion, and ambiguity. An even more profound formulation of their motto is: “Out-group diversity, such as nuanced thoughts and self-directed behaviors, activates a sense of inadequacy in me, through raising doubt on my shared belief system. Diversity, therefore, must be suppressed.”

Individuals with a foreclosed identity express a particular form of information processing known as the normative identity style. We referred to this in an autonomy development context as cognition for control, order, and certainty (Andringa et al., 2015). The normative identity style is a form of information processing that latches onto the familiar, the standardized, the expected, and whatever has direct utility (McGilchrist, 2012). As such, it prefers representations that have been stripped of ambiguities and have been made fixed, uniform, invariant, and static. And in its problem-solving, it denies inconsistencies and instead latches on to a single, normabiding, in-group-promoting solution, and an associated narrative that has been coupled with totalitarianism and authoritarianism (Beaumont, 2008; Berzonsky, 1989). The normative identity style of the foreclosed identity has been summarized as follows:

Normative individuals more automatically internalize and conform to the standards and expectations of significant others. Discrepancies between information about how they are and their normative standards evoke feelings of guilt and concern about avoiding failure [to be a good in-group member]. Their primary aim is to defend and maintain existing self-views [to protect a shared worldview that promotes coordinated action]. (Berzonsky, 2008, pp 646)

Normative individuals report high levels of identity commitment as well as dispositional characteristics such as agreeableness, conscientiousness [both facilitating rule following], and extraversion [promoting the adoption of the shared rules]. However, they also report low levels of openness and introspectiveness [which forecloses further identity development], Normative individuals have been found to employ avoidant coping strategies, to procrastinate in the face of [individual] decisions, to have a high need for structure and a low tolerance for ambiguity, and to be conservative, authoritarian, and racist in their sociocultural views (Beaumont, 2009, p. 97)

Karen Stenner (2005) summarizes the foreclosed identity’s characteristic urge to reduce complexity as “Intolerance to diversity = Authoritarianism x normative fear level,” where authoritarianism is a measure of identity foreclosure. She describes normative threats as threats to oneness (shared authority) and sameness (shared values and rules). In particular, she lists questioned or questionable authorities and values, disrespect for leaders or leaders unworthy of respect, and lack of conformity with or consensus in group norms and beliefs (Stenner, 2009, p. 143): all correspond to a disintegration of oneness and sameness. This summarizes the existential threat felt by those with a foreclosed identity when their only strategy to secure well-being — behavioral diversity reduction through (imposed) limits on agency — is frustrated. But when they do not feel threatened, people with a foreclosed identity manifest intermediate levels of well-being (Berzonsky & Cieciuch, 2016), since they are generally able to maintain problems and threats at manageable levels. All in all, this identity status expresses high coping adequacy and co-creation inadequacy.

The fourth identity status is referred to as identity diffusion and is characterized by inadequate co-creation and inadequate coping. People with this status live in a world of unprevented and unsolvable problems, with dynamics that they do not comprehend, with rules they do not know how to apply skillfully, and where effort and hoped-for outcomes are only weakly related. Given their low adequacy, their well-being depends predominantly on environmental factors. For people with identity diffusion the world is unpredictable and often brutal despite the best of intentions. Hence, they procrastinate in the face of self-decision and will not take responsibility for their actions.

Identity diffusion is characterized by prevented or avoided self-exploration in combination with a fluid or unstable self-identity. While aiming to improve their well-being, people with identity diffusion are often confronted with the consequences of their own inadequacy. Their intentions are good; their realization is not. And one often ends up in, or even self-perpetuates, low viability states. And without the benefit of self-exploration, they do not understand the causes of their problems. Much more than with the other identity statuses, people with identity diffusion live in a random (and brutal and unjust) world of problems in which they cannot take responsibility for their actions. This contrasts with achievers who live in a world of opportunities to be explored and responsibly realized. Beaumont and Pratt (2011, p. 174) describe the associated identity style thus:

A diffuse-avoidant identity style is associated with procrastination and attempts to evade identity conflicts and decisional situations as long as possible [all due to self-perceived inadequacy and mitigating efforts to prevent adverse outcomes and being exposed as inadequate]. … The use of a diffuse-avoidant style is characterized by low agreeableness, conscientiousness, introspectiveness, [complicating rule following] and cognitive complexity [indicating a shallow worldview], and high neuroticism. A diffuse-avoidant style is also associated with less adaptive cognitive and behavioral strategies, such as using avoidant coping strategies, engaging in task-irrelevant behaviors, expecting to fail, having a low feeling of mastery, and performing less strategic planning. [all indicating coping and co-creation inadequacy]

This description clearly demonstrates that people with a diffusion identity exhibit a narrow range of marginally effective or ineffective behavioral options that lock them into this status and curtail their well-being (Berzonsky & Cieciuch, 2016). They express both coping and co-creation inadequacy. Nevertheless, self-development occurs, and they can, although later than others, adopt narrowly effective strategies (towards the foreclosed identity status), develop self-exploration abilities (towards the identity moratorium status), or both (towards the achieved identity status).

In Section 3, we have connected the four combinations of co-creation, coping, adequacy, and inadequacy to the four identity statuses. The psychological literature has derived the properties of these statuses and the associated information-processing styles via careful experimentation and observation (in particular the copious body of research by Berzonsky). But to our knowledge, we are the first to derive the structural properties of identity from first principles (in fact, this might be a first for any phenomenon in psychology). This provides evidence that human psychology is indeed rooted in the core cognition shared by all life.

We also suggest a phylogenetic scaffolding which has coping and co-creation (as essentials of core cognition) as the foundation; identity status and associated information-processing styles building on this; and then personality traits like the Big Five on top. This is not new; two personality meta-traits, referred to as plasticity and stability (DeYoung, Peterson, & Higgins, 2002), have been proposed with a similar scaffolding model. More recently, DeYoung (2015) posited the underlying role of plasticity and stability in a cybernetic Big Five theory of goal-directed adaptive systems. This is similar to DeYoung’s proposal, although its goal-directedness suggests that it pertains predominantly to the coping mode.